Profile: Professor Krupa talks about working in music recording industry and journey to teaching

Richard Krupa’s wife was on the phone, and she seemed pissed.

Well, that’s at least what all of his co-workers at the Polygram Records office thought. Whoever was on the other end definitely wasn’t happy, that much was true… but only Krupa knew who he was actually dealing with as he went to go take the call.

It was Elaine Irwin — supermodel wife of John Mellencamp, the future Rock and Roll Hall of Famer behind such hits as “Jack & Diane” and “Pink Houses.” Krupa just happened to be the unlucky record salesman in charge of managing the accounts for Johnny Cougar’s home state of Indiana.

“She would hire kids in Indiana over the weekend just to check the Mellencamp bins [at record stores],” Krupa said. “And then, every Monday, she would call me at the office to yell at me: ‘Why doesn’t this store have Lonesome Jubilee?’”

This was all happening smack in the middle of the 1990s: Mellencamp was far from washed up, still selling out concert venues and releasing singles that kept his name in the Billboard Hot 100. And yet, the calls continued.

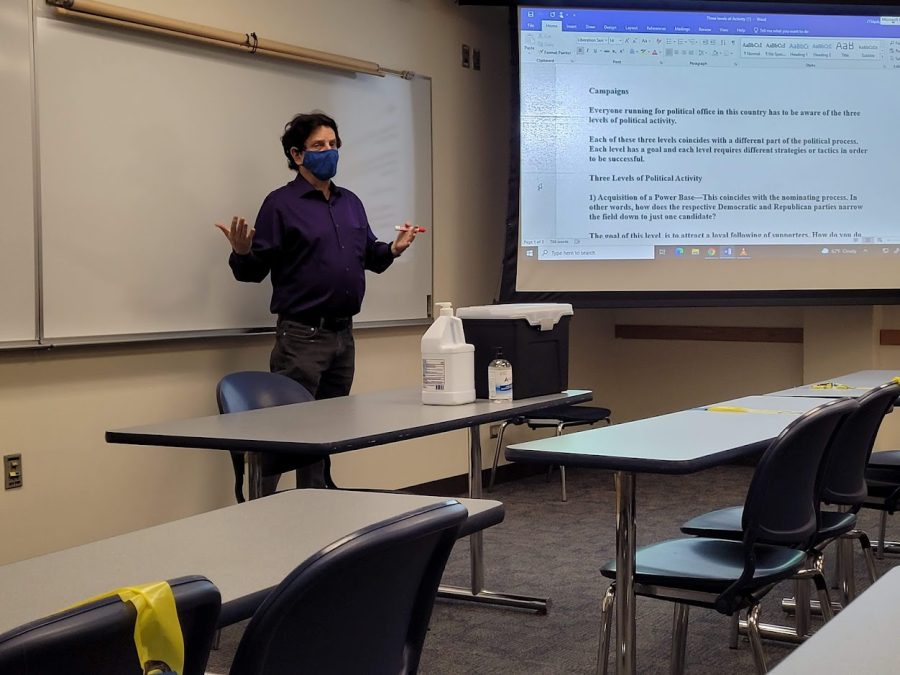

Flash forward to 2021 — Krupa traded record stores for classrooms a long time ago, but his work as an adjunct professor of political science for Harper College (as well as many other Chicagoland schools such as National Louis and Roosevelt) has kept his phone ringing much in the same way.

Except now, instead of supermodels and rockstars, the incessant complaining comes from C+ students asking for A+ grades, or young conservative firebrands who are convinced their academic decline is a result of bias against their beliefs.

Despite that, there is one hell of a silver lining to dealing with students over dealing with sales accounts.

“Even the worst student you have as a teacher, you kinda have to keep it in the back of your head that, in a couple months, this kid is going to be gone!” Krupa said. “So I don’t have a lot of sleepless nights regarding school [like I did] when I was worrying about making quotas.”

Krupa isn’t oblivious to the other parallels, and his teaching style reflects that. There’s a consistent candor to the way he talks, even when he goes from explaining the ins-and-outs of a complex political theory to telling one of his many anecdotes from his time in the music business. He maintains a lively and straightforward energy, never afraid to crack a joke or explore a tangent to its appropriate conclusion.

“Maybe that’s why I was able to make the transition so easy. It’s a little like giving my students a pitch every week,” Krupa said.

In a sense, this transition has been a lifelong one — something that had been at the back of his mind for a long time.

Krupa first graduated from Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin with a bachelor’s degree in political science. However, that career path wasn’t the initial expectation of neither Krupa nor his family.

“I started college as a chemistry major because my father was a pharmacist […] So there was some talk about me one day taking over the pharmacy,” Krupa said. “But my first chemistry class was just way too difficult, so I just said, ‘What’s the easiest thing I’m taking right now?’ and [the answer] was: ‘Oh, political science!’ Little did I know I would make a career out of it!”

Krupa maintained a keen interest in politics throughout college and beyond, citing his poli-sci professors from this time as the blueprint for his current teaching method. However, his fascination with music — and the industry behind it — had there for long as he could remember. He had grown up in the mid-sixties with an older sister who had a near-terminal case of Beatlemania. His house was littered with posters of the Fab Four, along with other popular acts like Paul Revere & The Raiders and Herman’s Hermits. This interest continued into high school and college, where concerts became a treasured pastime — not only did big names like Alice Cooper and Bruce Springsteen draw Krupa to the shows, but also the sense of intrigue about all the behind-the-scenes work necessary to keep such names in the spotlight.

“Throughout college, I was trying to find out how to break into the [record industry],” Krupa said. “I knew I had no musical talent, but for me it was all about the business side of things anyway. And I couldn’t quite figure out the way to do it, I didn’t have any connections or anything like that.”

Krupa’s first attempt to find a way in was through joining the concert committee while he was enrolled in Marquette — it didn’t exactly pay dividends when it came to industry connections, but it did give him a taste of what the future had in store when it came to working with talent. Memorably, he had to escort a very drunk Dave Mason fame to a show from the airport. The English singer-songwriter and founding member of Traffic was “completely wasted,” with only three questions on his mind: “Where am I? Are there women here? … Do they put out?”

Once his time at Marquette was up, however, his political science degree was not doing him much good in the job market. Again, his music aspirations took precedence, and Krupa found himself working at Kroozin’ Music, a record store in Chicago.

“Minimum wage back then must have been five or six dollars an hour, so my parents were real proud of me,” Krupa said. “All that money for education, and I’m mopping floors and stocking shelves at a record store.”

Still, despite the not-quite-a-living he was making, Krupa kept the big picture in mind. Sales representatives from record companies were in and out of Kroozin’ Music constantly — setting up promotional displays, brokering sales with management, and even booking an occasional in-store appearance from artists on their label. Krupa made it a point to talk with salespeople as much as he could in order to start making those connections.

“I think that was my ultimate goal, to work for a record label — but there was a process to getting there,” Krupa said.

But before he could begin that process to its fullest extent, he was given an opportunity: Marquette was offering him a scholarship if he were to return and continue his studies for a master’s degree. So from ‘82 to ‘84, Krupa immersed himself in the world of political science yet again — all the while knowing full well that as soon as he graduated he was going to return to his job at Kroozin’ Music to finish what he started there.

Actually it was life after music that motivated him to go back to school.

“I think, even back then, I knew I’d end up teaching [one day],” Krupa said. Now with his master’s degree in tow, he could truly begin his climb up the industry ladder. Shortly before Kroozin’ Music was shut down by the IRS for tax evasion (an inevitability Krupa said he saw coming way ahead of time), he was offered a job from one of their suppliers, a “one-stop” in Niles called Baker & Taylor, which mostly sold videos and music to lower-rung record stores that couldn’t afford to buy directly from distributors.

Initially, he was part of their customer service department, but before long he was promoted to the role of buyer — a role with “a lot of power” according to Krupa, as they had complete control over not only what records to buy, but how many to stock.

“Let me put it like this: it’s all guesswork … It’s like a constant battle with numbers and data sheets,” Krupa said. “[But] in return for me bringing in [records from certain companies], they’d say, ‘Hey, do you want tickets to a show?’ … I learned really quickly that [Columbia Records] had a suite at the United Center — for everything! Not just for concerts, but for the Bulls and the Blackhawks.”

As Krupa moved further on up — from Baker & Taylor to a record distributor called Navarre, and then from Navarre to major label Polygram in 1990 — he’d learn that these transactional sorts of relationships were the bread-and-butter of the industry. It’s how salespeople interacted with record stores, with concert venues, even with other salespeople from rival companies.

His career as a sales representative at Polygram was during a diverse period in popular music. The various artists signed under Polygram and its affiliate labels ranged from U2 to Janet Jackson, from Def Jam to Pavarotti. Lots of deals Krupa would make to his different sales accounts would bring him into close contact with these celebrities — and because it was such a diverse period, the quality of such experiences were all over the place.

Krupa has fond memories of working artists like Montell Jordan, Sting and Melissa Etheridge, the last of which he worked with extensively. But the bad experiences speak for themselves, and Elaine Irwin with her many calls was just the tip of the iceberg.

There’s the time that David Bowie hocked a loogie and put out a cigarette into a cooler full of water bottles. Then there’s the time Krupa had to drive Redman from Chicago to Milwaukee, only for the rapper to refuse to enter the store he’s scheduled to appear at because there weren’t enough black people inside.

And then there’s the time the lead singer of Ugly Kid Joe ditched Krupa at an in-store event to go buy himself mashed potatoes for lunch, only to return later and declare the whole inventory of the store free — and that was all before he caught a lawsuit for some horrible comments he made live on air on a local radio station broadcasting from that very same building.

But of course — as backstage as his work was — this was still show business, and the curtains needed to be called eventually. Krupa would continue working with Polygram throughout the ‘90s until the company was acquired and merged into Universal Music Group. In 1999 the company began laying off salespeople, and despite being amongst their top ten salespeople in terms of numbers, Krupa found himself on the chopping block.

“That was a huge blow to my ego, because I was sort of the king of my own little world. Anything I wanted I could get, because I made friends with all the other sales reps from all the other record labels. … I’d call up my friend at Warner Brothers: ‘Hey, could I get some Tom Petty tickets? I’ll give you John Mellencamp tickets!’” Krupa said. “It was all about these trade-offs … [but now] I lost my gig.”

Six months later, Krupa found himself in sales once again, now working from home with a considerably smaller Florida-based company called Innovative Distribution Network (IDN). “I wasn’t sure how long this company was going to exist, because basically they had junk,” Krupa said. “The music industry was changing. 2008 and 2009, MP3s were coming onto the scene and record stores were closing. And I kinda saw the writing on the wall. … It was going away from physical goods, physical marketing, which is what I always did.” Krupa called himself “the last man standing” at IDN, sticking it out with the company until its closure in 2013. But seeing as he was working from home, he had started to scout out alternative career paths as early as 2007.

It was then that he saw an ad in the Chicago Tribune for an adjunct political science teaching position at Morton College in Cicero, Ill.

He didn’t have any experience as a teacher, but nonetheless he sent in an application, thinking little of it beyond the chance that his master’s degree might give him an edge. When he got called back for an interview, he had no idea what to expect… and even less of an idea after a dean from the school gave him the job right on the spot.

“You were the only one who handed in your college transcript,” she told him. From 2007 up until IDN closed, Krupa had one foot in each world, working adjunct positions at many schools while also doing sales for IDN. But with each passing year, the music industry continued to slip into the digital age. It took time to get used to this new career, but eventually, he realized that it didn’t change what he had to do for a living — it only changed who was calling his phone every Monday morning.

“Teaching is a sales job in and of itself,” Krupa said. “The students have paid money. They’re trying to get something out of the tuition they’re putting in, and [it’s up to me] to sell them on my abilities as a teacher and on the material that’s presented in the class.”

.