A tribute to the deaf professor who was all ears

As a child, Elke Weinbrenner was “stubborn, trouble” and “combative,” according to her father, Leeroy Weinbrenner.

Growing up as a deaf and queer person in a predominantly hearing and heteronormative world, Elke was constantly trying to find her way in an environment that wasn’t built to accommodate her.

Leeroy said she frequently had to put up with biases against deaf people, such as the misconception that deaf people are dumb, and she didn’t tolerate that well. Although she cooperated with kids in her neighborhood, she often wanted to have things “on her own terms.”

As Elke grew older, her stubbornness grew more subtle, according to Leeroy. However, she was meticulous about researching her desires and never took “no” as an answer.

“I would guess that some people would interpret that as stubbornness,” Leeroy explained. “I would say it’s more like working hard towards achieving what you believe in.”

And that’s exactly what Elke did. Throughout her time as an American Sign Language (ASL) professor at Harper College, Elke fiercely advocated for marginalized communities, proving her perceived “stubbornness” to be a commitment to creating a more just tomorrow.

She passed away in November 2020, but her legacy will live on through her advocacy work.

According to LaVonya Williams, a member of the counseling faculty, and Jason Altmann, Director of Access and Disability Services, Elke was one of the original advocates for establishing a system at Harper to help students with chosen names have their preferred names show up on all their school records.

Williams noted that she was also involved in the committee to help bring gender-neutral bathrooms to Harper and said she covered a lot of ground in the areas she was passionate about.

“That was the gift, but that’s also the loss, and [for] those that worked with her closely like myself, that is what inspires me or empowers me to continue to work,” Williams said.

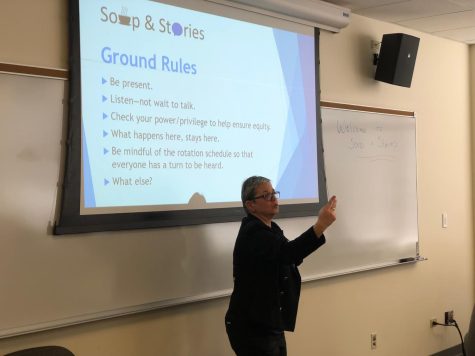

Williams worked closely with Elke to coordinate and facilitate Safe Zone training at Harper, which is a program that educates people on how to support members of the LGBTQ+ community.

She described this experience as one of the highlights of her career. As someone who is both African American and queer on a predominately white campus, working with Elke, who understood the experience of having multiple marginalized identities, provided her with a sense of safety.

“To do these trainings and really share this other side of me is not the easiest thing to do. It’s very vulnerable. So having Elke there with me, it made it easier,” Williams recalled with tears in her eyes.

Linguistics professor Alina Patjek also connected with Elke through having a marginalized identity. Being an immigrant from Romania, she shared common ground with Elke as a minority while also being able to learn new things from her.

“It was exciting for me to see her worldview and to understand her perspective,” Patjek said.

Elke’s inclusiveness was apparent not only through her work but also through her actions in everyday life. Many who were close to her described her as “supportive” and a “good listener.”

World Languages, ESL and Linguistics professor Kimberly Jaeger had her office next to Elke’s and recalled that Elke would always make a point to check in with her daily to say hello, ask how her day was and sometimes share something exciting. They would also compare pictures of each other’s dogs, and Jaeger always looked forward to receiving an “Elke hug.”

“A big hug from Elke just made anybody’s day brighter,” Jaeger said.

Altmann also commented on Elke’s empathy. If he was having a bad day, he would often reach out to her because of her ability to listen and provide a different outlook on situations.

“She just showed that she really cared about everyone and who they are as individuals,” Altmann said. “She never judged anyone, and that’s why she really left a legacy where she really wants everyone to feel included and accepted for who they are.”

Leeroy recalled that Elke regularly went grocery shopping either for or with him and her late mother, Joyce Weinbrenner.

“… she was just one of those kinds of very supportive people,” Leeroy said.

Karla Weinbrenner, Elke’s sister, commented on the fact that Elke would put everyone else’s needs before her own.

“I was giving her a hard time. I’m like, ‘You know, you can say no sometimes,’ because she always had so much on her plate. And she’s like, ‘No, they need me. I can’t,'” Karla said. “I’m like, ‘You need to take care of you too.’ I just never realized how many people she impacted and how many people appreciated her. I know there’s a lot of people that miss her.”

Despite Elke’s humble nature, she was not one to shy away from the spotlight.

Jaeger remarked on Elke’s performance in a deaf version of The Vagina Monologues at Harper. According to Jaeger, The Vagina Monologues is a traveling show centered around women’s experiences, including sensitive topics such as gender, sexuality and sexual violence, as well as the idea of women celebrating sex.

Elke worked with colleagues from other organizations to create a deaf version of the show at Harper. All of the actors cast were deaf and performed through ASL, and there were interpreters who translated the performance to spoken English for hearing audience members.

“She was a really good actor, a really good actress, and … I was amazed at her confidence and her ability to act,” Jaeger said.

Williams also saw Elke’s version of The Vagina Monologues and noted that Weinbrenner captured her attention.

“You could pick her out of everyone on stage, she stood out just because of that brightness around her energy,” Williams said.

Elke’s energy was equally as dynamic in the classroom, as Harper graduate Brianna Roldan can attest to. Roldan, who was born deaf and has communicated through ASL her entire life, assisted Elke with her ASL classes.

“She’s always big and outgoing,” Roldan said. “And she always signs so big. That’s what I like about her too. Because there’s some people that would just sign smaller, inner, you know. But Elke’s more outgoing — signs really big.”

Harper graduate Adam Lyke, who took a couple of classes with Elke and interacted with her in various clubs such as ASL Club, Deaf Club and Pride Club, remembers her care for others.

“I think she was always finding time to be there for anyone,” Lyke said. “That’s why we are able to connect together really well.”

A memorial for Elke took place on April 27, 2022, in Building D. After several colleagues and students spoke to reminisce on their memories with her, the provost presented a plaque dedicated to her outside the Cultural Center. Artifacts and photographs of Elke were displayed inside for attendees to look at.

Elke will be greatly missed by her family and many Harper faculty, staff and students. In regards to continuing her legacy, Karla made a statement:

“I just really want people to continue on with her dreams and to be the most authentic version of themselves,” Karla said.

To help remember Elke, you can donate a tribute gift for her through the Education Foundation. You can choose to designate your gift to PRIDE Club’s Audrey Howard Memorial Scholarship, ASL Club’s Deaf and Hard of Hearing Scholarship, a paver honoring Elke or a cause of your choice.

Adriana writes feature stories, news stories and editorials for The Harbinger.

Jeff Przybylo • Feb 4, 2023 at 6:23 pm

Great tribute. We miss you Elke

Jeff Przybylo • Jan 17, 2023 at 12:05 pm

She was such an amazing person. Thank you for writing this incredible tribute. And if anyone reads this, don’t forget to contribute to the educational foundation scholarship in Elke’s name.