Why you should watch foreign films

About a year ago at a small family get-together, my cousin and I were discussing movies we had recently watched.

I mentioned a few Wes Anderson and Stanley Kubrick movies I had enjoyed, thinking myself a hardcore film connoisseur for having seen Dr. Strangelove and Rushmore. She proceeded to ask if I had heard of or watched Irreversible by Argentinian director Gaspar Noe and offered a brief description of this hyper-violent film told in reverse after I said I hadn’t.

She also provided a trigger warning about it containing a graphic sequence of sexual assault before adding, “It’s in French, so if you’re not big into subtitles, it might not be for you,” afterward.

Having never been averse to subtitles before, and being intrigued by my cousin’s pitch, I watched Irreversible for free on Tubi the first chance I had when I got home. Despite its graphic and incredibly upsetting nature, I couldn’t help but be pulled in by just how different it was from anything else I’d ever watched before; never mind the fact that it was my first French movie.

I knew from that moment that I needed more — more variety in the kinds of stories I was being exposed to in film, and the techniques being employed to tell said stories.

While the rest of the world learned to bake sourdough and played Animal Crossing (both being worthwhile hobbies, mind you), I spent my lockdown becoming immersed in the extensive world of foreign movies, and I think you should give them a try too.

When proposing the idea of watching films from another country, a common complaint I’ve heard from people is that they don’t want to read subtitles.

The reasons they cite are that they find them too distracting, or that they can’t keep up with the text while paying attention to the action on-screen at the same time. The solution I would propose to this problem is to just throw yourself in and practice reading subtitles on any piece of foreign media you’re interested in. Chances are, you’ll pick up on the skill faster than you originally thought you would.

Something I find valuable about having subtitles on the screen for a movie not in my native language is that it forces the viewer to really pay attention to what they’re watching. You can’t check your phone while listening to a scene of dialogue like it’s a podcast and still get the gist. You must be an active participant during the entirety of the film to completely understand what’s happening, and you’ll likely develop a more complete understanding of what you’re watching as a result.

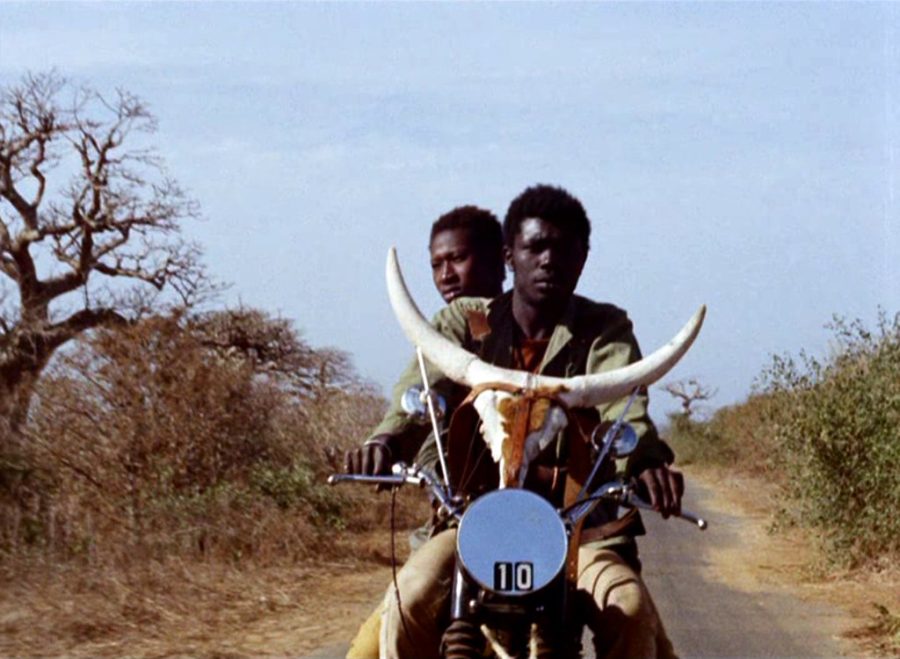

Watching movies from different cultures is also a great way to build empathy for those different from us, and a great way to learn a bit about them. When I watched the movie Touki Bouki by Senegalese director Djibril Diop Mambéty, I was introduced to a whole way of life unlike any I had seen presented on camera.

The story follows a Senegalese man and woman named Mory and Anta on a journey to escape from the poor conditions of their country and board a boat to France. The only thing standing in their way, of course, is money, or more specifically their lack thereof.

Despite the low budget of the movie, as well as the more impoverished settings which are the focal point of the story, I found myself drawn into the natural beauty of Senegal presented on screen as well as its unique culture which Mory has reservations about abandoning; an aspect of his character that becomes a major point of conflict later in the film.

I am in no way saying that watching Touki Bouki has made me an expert on all things Senegal, or that watching movies from a particular country is a substitute for taking the time to really learn about or even visit them. Far from it.

I will say, however, that absorbing stories from countries other than my own has caused me to reflect on myself and the world that I live in far outside the immediate one I inhabit and sparked an interest in the reality that art came from. Watching foreign films has been a sobering reminder that the world is, and always has been, so much bigger than we often feel it is, especially when we’ve been stuck in our homes for so long.

I don’t just enjoy foreign films because of the new cultures and settings they introduce me to, however, but also because many of them have given voice to feelings I’ve felt more effectively than ones in my native language. Take for example the 2019 film We Are Little Zombies, by Japanese director Makoto Nagahisa.

We Are Little Zombies centers around a group of four children whose parents have died on the same day and meet at their funerals by chance. Distraught at the fact that all four of them feel little after their parents’ demise, they do the obvious and form “a kick-ass band,” as one of its members aptly proposes, in an effort to make money and somehow find their “lost” emotions.

Watching these four children grow up together and attempt to externalize their grief reminded me of my own struggles with expressing turbulent emotions. Stewing in such feelings can often cause us to feel alone in our way of thinking and convince us that we are the only ones who feel this way.

Observing a movie from more than halfway across the world reflect the way I often feel reminded me that our experiences as humans are more universal than we think, regardless of linguistic, cultural or geological differences.

So instead of watching the latest flick starring The Rock or Ryan Reynolds this weekend, try stepping outside of your comfort zone. Seek out those deep cuts on Netflix or Hulu that you would have glossed over before. You may be surprised at just how much you get out of it.